Content-Based Filtering

All techniques introduced Collaborative Filtering rely on not only target user's historical behavior on a service, but also the other users' actions. However, these kinds of recommenders easily fail due to the lack of aggregated data, and there is no way to make meaningful recommendation for new items. In order to work around the difficulty, content-based filtering is likely to be preferred in reality as discussed by Lops et al.

Most importantly, content-based recommenders make recommendation without using the other users' feedbacks. In the related studies, "content" indicates a set of item attributes (i.e., features or descriptors), and the content-based recommenders can take advantage of richness of item attributes on a real-world service, instead of tracking users' actions. The recommenders, therefore, strongly focus on modeling items by assuming that users' preferences are not change dramatically over time.

In particular, a content-based approach gives scores to items based on two kinds of information: item model and user preference. In order to model the items, an item-attribute matrix is defined as: $I \in \mathbb{R}^{|\mathcal{I}| \times |\mathcal{A}|}$, where $\mathcal{A}$ is a set of item attributes. Moreover, we can also construct users' profiles for the attributes by $U = RI \in \mathbb{R}^{|\mathcal{U}| \times |\mathcal{A}|}$, where $R \in \mathbb{R}^{|\mathcal{U}| \times |\mathcal{I}|}$ is users' past feedbacks to the items. Each row of $U$ denotes a vector of attributes describing user's profile. Note that the number of items and their attributes should be large enough on a content-based recommender. The systems do not necessarily need to have so much users instead.

Recommendation.TFIDF — TypeTFIDF(

data::DataAccessor,

tf::AbstractMatrix,

idf::AbstractMatrix

)Content-based recommendation using TF-IDF scoring. TF and IDF matrix are respectively specified as tf and idf.

More concretely, each item is represented as a set of words, and the items are modeled by TF-IDF weighting of the words. The technique was initially used in information retrieval to model a document-word matrix. In case of our item-word matrices, for a given item $i$, term frequency (TF) for a term $t$ is defined as:

\[\mathrm{tf}(t, i) = \frac{n_{t,i}}{N_i},\]

where $n_{t,i}$ denotes an $(i, t)$ element in $I$, and $N_i$ is the total number of words that an item $i$ contains. So, $\mathrm{tf}(t, i)$ characterizes an item-term pair by normalized frequency of terms. Meanwhile, inverse document frequency (IDF) is computed over $M$ items as:

\[\mathrm{idf}(t) = \log \frac{M}{\mathrm{df}(t)} + 1,\]

where $\mathrm{df}(t)$ counts the number of items which associate with a term $t$. What $\mathrm{idf}(t)$ does is to decrease the effect of commonly used terms, because general words cannot characterize a specific item.

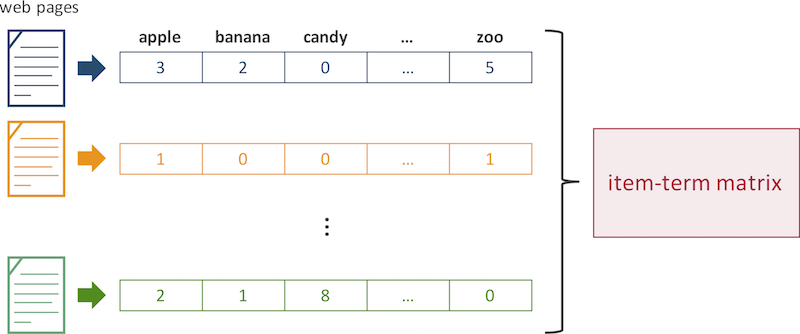

Finally, each item-term pair is weighted by $\mathrm{tf}(t, i) \cdot \mathrm{idf}(t)$ in the TF-IDF scheme. For instance, if we like to recommend web pages to users, we first need to parse sentences on a page and then construct a vector based on the frequency of each term as follows. Similarly, in case that a recommender is running on a folksonomic (i.e. social tagging) service, the frequency of tags corresponds to each dimension of a vector, and $\mathrm{tf}(t, i)$ and $\mathrm{idf}(t)$ are finally calculated for each item-tag pair.

From a practical perspective, designing attributes is essentially an important problem to launch a content-based recommender successfully. In fact, there are numerous attributes which can be incorporated into a vector space on a real-world dataset, but using too much attributes may increase sparsity and complexity of the vectors. As a consequence, inappropriate vector representation of items may show poor recommendation accuracy. Hence, we need to carefully design a vector to distribute the attributes equally.

If the features were chosen appropriately, content-based recommenders could work well even on challenging settings which cannot be handled by the conventional recommenders. To give an example, when a new item is added to a system, making reasonable prediction for the item is impossible by using the classical approaches such as CF. By contrast, since content-based recommenders only require the attributes of items, new items can show up in a recommendation list with equal chance to the old items. Furthermore, explaining the results of content-based recommendation is possible because the attributes are manually selected by humans.

For the reasons that we mentioned above, vector representation of item attributes and content-based recommendation are practically important strategies for real-world recommendation.